Legal differences in the treatment of objects and liabilities

"An object has its own distinguishing signs, the most important

of which is the externally expressed material form of

an object."

D. V. Murzin 21

There is a clear difference between property laws and liability laws.

The application of either standard is mutually exclusive.

When jus ad rem grants its bearer the opportunity to directly exert

influence upon it (when the object of the law is the article), the law is

called proprietary. In Rome, property law was closely related to proprietary

interest, and ownership and other laws on other people’s articles

are closely linked to them. In cases where the subject has no direct right

to an article, but has only the right to demand that another party gives

him an article, this law is called contractual. Thus, differences between

proprietary and contractual laws develop according to the object of the

law: if the object of a law is an article, then we are dealing with proprietary

law; if the object of a law serves the action (or abstention from

action) of another party, but the subject of the law may only demand that

an agreed action be completed (or abstention from the action), then this

is contractual law. In other words, various civil legal relations correspond

to defined groups of objects of civil rights. From this perspective,

differentiation between property and contractual laws holds great significance,

as it predetermines the differences in legal conditions for

concrete objects.

Unfortunately, nowadays attempts to merge the different legal procedures

are not uncommon. Instead of onerous concessions of rights,

attempts are made to «buy and sell» «uncertificated securities», and to

consider shareholders as «holders of rights» to shares and «to rent interest

in land» 22.

The classification of property rights into proprietary and contractual

is not referred to among Roman lawyers, who spoke only of the

differences of property suits (actiones in rem) and personal actions

(actiones in personam). The differentiation between proprietary and

contractual laws was worked out later by legal experts, though based on

the materials that Roman lawyers had had. Nevertheless, the latter paid

attention to the fact that the legal position of a party holding proprietary

rights to an article and the legal position of a party entering into an agreement

with the owner of an article to the effect that the latter is obliged

to give him the article for temporary use are not the same. In the first

case, the owner has the opportunity to directly exert influence on the

article — to use it, destroy it, transfer it to another party, and so on

(‘directly’ in the sense of independently from any other party). In the second case, the debtor’s rights to the article are limited, firstly by the

period of use which he has agreed with the owner (or the time when the

latter demands the article, if a concrete period of time has not been

stipulated), and, secondly, the need to return the article (that is, he may

not destroy or sell it).

The principal difference between the transfer of property rights (the

establishment of easement) and a party’s acceptance of the obligation

to transfer ownership of an article (carry out another action) lies in the

fact that the obligation of one party to grant another ownership of a

known article does not immediately create property rights to this article

for the other party. Only as a result of fulfilling such an obligation and

under other necessary conditions does the party who has acquired the

article become its owner. Only the right to demand transfer of the article

springs directly from the obligation. Therefore, the party who bought

the article still does not become its owner even on condition of payment

of the purchase price. This party only has the right to demand transfer

of the article to him, and only becomes the owner after the article has

actually been transferred and on the condition that the person who

transferred the article had property rights to it.

Thus the difference between proprietary and contractual laws that is

accepted in modern civil law, is also found (conditionally) among the

Roman lawyers. As a result of this difference in the object of law the difference

in defence arises, which Roman lawyers expressed as a contrast

between property and personal actions. Modern law has come up with two

categories to express this idea: absolute and relative (Table 1).

This idea is based on the following principle: legal relations for

ownership of material goods by specific parties have an absolute nature

— the authorised holder of right is in opposition, so to speak, to

an undefined group of individuals (by all other parties) who are obliged

to refrain from any infringements of the law against his property and

not to hinder the realisation of his rights. The Roman legal experts also

considered that, since the object of proprietary interest is a physical

item and anyone can encroach upon it, proprietary interest must be

defended against every infringer of the law, whoever it may be; proprietary

interest is used as an absolute defence against a personal action.

In contractual law, a party may request an individual or several precisely

defined individuals to execute a particular action. Therefore, infringers of contractual law are either one party or several specific

parties, against whom the subject of the law may bring a personal action.

Here, protection of contractual law is of a relative nature.

Having rented out a material object, the owner does not lose his

property rights to it. When intangible and immaterial receivables are

transferred, the creditor simply «quits», his relationship to this right

ceases, he completely withdraws from the legal relations.

Both in Roman and modern civil law, from the very beginning, a contractual

legal relationship was seen at its natural end as a means of fulfilling

a certain action within the fixed deadline. It differs in this way from

property rights, established for an indefinite, extended period of time. In

cases where a debtor deliberately does not fulfil his duties, the creditor

is granted legitimate means, that is, established by law, of compulsorily

realising his right of demand. Such a method of forcing the debtor

to satisfy the demands of the creditor under a commitment in Rome

was a personal action or forced penalty. Ancient Roman lawyers also

defined a debtor as a party who whose debt could be recovered against

his will.

Legal standards are a particular kind of judgement. Their content

reflects the wishes of a legislator in that duty of fulfilment about which

there is no doubt. In this sense, legal standards are true judgements.

But a judgement with internal necessity turns into a deduction which

is used to justify the judgement. «The transition of a judgement into a

deduction, which is a justification of its grounds, is a synthetic link,

a definite system of seniority, which is also a logical development»23

| Criterion |

Proprietary interest |

Law of obligation |

| Object |

Article |

Right to demand execution

of an action (or abstention

from it) |

| Influence of the

right-possessing

party |

Direct |

Request for influence |

| Nature of legal

relations |

Absolute — with regard to

everything |

Relative — with regard to a

strictly defined party or

group of individuals |

| Number of rights

with regard to object

of law |

Trio of competences:

Instruction

Ownership

Use

|

Single competence: Request for defined action to

be executed |

| Status of object of

law |

Complex:

Belongs to X

In possession of Y

Used by Z

|

Simple: Exists or does not exist (logically — 1 or 0) |

| Period of legal

relations |

Indefinite (perpetual) |

Definite (as a rule) |

|

Situations that arise in the course of the logical development of normative

judgements must obviously also not provoke doubt with regard to

wishes concluded in them. The will and intention of a legislator, developed

as a chain reaction — «judgement-deduction-judgement» — are

as reliable as their primary element — the standard of law, although we

must still always proceed from the fact that in publishing a normative

act, a legislator has thought through all its logical and factual consequences

and conclusions at which a body that applies the law may arrive.

Drawing from the definitions:

an entity is an object belonging to the material world;

an obligation is the right to request a certain person to carry out

certain actions or to refuse to do so.

The right to request is immaterial; an entity, material.

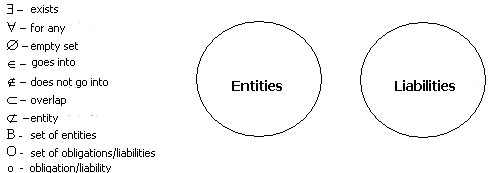

Speaking in terms of logic, many entity-objects and liability-objects

do not overlap, or the application of property or contractual legal standards

are mutually exclusive.

We shall note:

Correspondingly, the rules of circulation for entities must also be

applied to liabilities. Is it really possible to have a right of ownership to

a right of demand? Is it really possible to give to whomever the right to

temporarily use a right of demand? E. A. Sukhanov believes that «objects

of property rights are a narrow concept, encompassing only goods,

i.e. items belonging to the material world.»24.

Either there is a right of demand, or there is not. It can be transferred,

but for several people to use such a right at the same time is not

possible, since it draws twice as many rights and corresponding obligations

without agreement with the creditor upon a commitment.

Dualism of proprietary law and contractual law is caused by the

absolute non-identity of an article and a person.

There are principal differences in the treatment of objects and liabilities.

Property rights, ownership, holding property, and instruction to right

of demand cannot exist, as the right is not a material object.

Personal actions are not applied to obligations, and suits forcing

fulfilment are not applied to goods, as goods cannot be compelled to do

anything — they are not spiritual beings.

In institutionalism and neo-institutionalism, the position conveyed

by Coase prevails, that on the market, material goods themselves do

not circulate, but rather bundles of rights to them, and it is precisely

these bundles of rights that reveal the real relations between economic

subjects in regards to material goods.

Let’s consider some examples of the formation of bundles of rights

with a monetary loan as an obligation and as an article.

An example of the formation of a bundle of rights with a monetary loan

as an obligation.

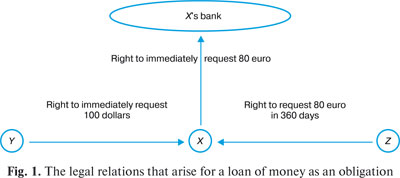

Let us assume that a certain X borrowed 100 US dollars from Y in

non-cash form for a term of five days and lost them on the second day.

On the third day X borrowed 80 euro from Z in non-cash form for a term

of one year (taking an exchange rate of 1 dollar to 0.8 euro). On the sixth

day there are the following legal relations — bundle of rights (Fig. 1):

- contractual — X is obliged to pay Y 100 US dollars in non-cash

form immediately;

- contractual — X is obliged to pay Z 80 euro in non-cash form in

360 days’ time;

- contractual — the bank is obliged to pay X 80 euro in non-cash

form on demand.

Protecting his rights, Y has the right to demand satisfaction from X’s

assets, which is expressed in the form of the right of immediate demand

to the bank for 80 euro, which the officer of the court on the decision

of the court withdraws by coercion from X bank and transfers to Y

bank.

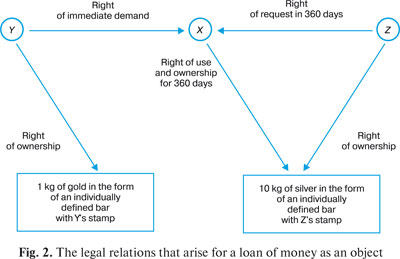

Example of the formation of money as an object.

Let us assume that a certain X has borrowed from Y 1 kg of gold in

the form of an individually defined bar with Y’s stamp for a term of five

days and lost it on the second day. On the third day, X borrowed from Z

10 kg of silver in the form of an individually defined bar with Z’s stamp

for a period of one year (taking an exchange rate of 1 kg gold = 10 kg

silver). On the sixth day, when the deadline for payment by X has come,

there are the following legal relations — bundle of rights (Fig. 2):

- proprietary — Y has the right of ownership to 1 kg of gold in the

form of an individually defined bar with Y’s stamp;

- contractual — X is obliged to give Y 1 kg of gold in the form of

an individually defined bar with Y’s stamp immediately, as the period

of temporary ownership and use has elapsed;

- proprietary — Z has the right of ownership to 10 kg of silver in

the form of an individually defined bar with Z’s stamp;

- proprietary — X has the right to own and use 10 kg of silver in the

form of an individually defined bar with Z’s stamp for 360 days;

- contractual — X is obliged to give Z 10 kg of silver in the form of

an individually defined bar with Z’s stamp in 360 days’ time.

Protecting his rights, Y does not have the right to demand satisfaction

from X’s assets, which are expressed in the form of 10 kg of silver

in the form of an individually defined bar with Z’s stamp, since the right

of ownership to these 10 kg of silver belongs only to Z, and nobody

except the owner has the right to remove this article from X25 .

These examples demonstrate the formation of different bundles of

rights and the difference in handling money in proprietary and contractual

form, thus showing that different forms of treatment exist for

different forms of money.

|